[Dedication: This piece is dedicated to a dear friend and law school mate, Richard Badombie Esq whose tragic passing at the hands of some armed persons has left us in shock. He would be sorely missed for his public spiritedness and warm personality]

The early days of law school was difficult. It required getting used to the case law method of teaching and learning. And adapting to the workload. There were too many cases to cram and little time to reflect.

As quickly as cases were read, they were forgotten. But despite all this, a few cases make an impression on you. And this remains with you for a long time. The Republic v Director of Prisons, Ex parte Salifa[1] was one of those cases for me.

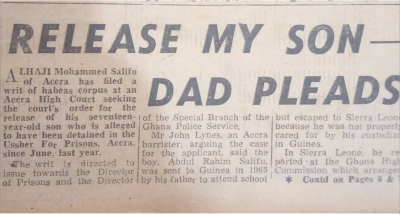

Put the legal complexities, and jargons away and this case is simply about a child in the grip of the State and a father yelling and doing all he could to have his son back. Nothing is said of what the child is suspected of. But it was widely believed the boy was being held on the charge of subversion.

To better appreciate this story, let’s start with the overthrow of Ghana’s first President, Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah. This was in 1966. A group of senior military and police officers led by Lieutenant General (retired) J.A. Ankrah led a coup to overthrow Ghana’s first president. Kwame Nkrumah, by then had left Ghana and was on his way to Hanoi, at the invitation of the Vietnamese Leader, Ho Chi Minh. After a number of stop overs, Nkrumah finally settled in Hanoi. It would not take long for news of his overthrow to reach him on 24 February 1966. It was not something Nkrumah saw coming. On 25 February 1966, Nkrumah through his Foreign Minister, Mr Alex Quaison Sackey, declared that he was still the Head of State of Ghana and that he would return soon.

Nkrumah must have known that returning to Ghana was not an option. He flew to Moscow and then from Moscow to Conakry, Guinea. This was on 2nd March 1966. There, he was made a co-President. The choice of Guinea was not strange. Nkrumah had been generous to Guinea. In 1958, Nkrumah lent 5,000,000 pounds to Guinea, and Guinea’s reciprocity was understandably natural.

And it was on this day, 2nd March 1966, that Nkrumah would make a speech that would not only put a strain on the diplomatic relationship between Ghana and Guinea. It would, probably, change the life of a boy – forever.

When Nkrumah arrived in Guinea, he declared:

“I have come here purposely to use Guinea as a platform to tell the world that very soon I shall be in Accra, in Ghana. I am not going to say anything against anyone, because I understand perfectly the factors at work in the world today… All we have to do is to stand firm and see how we can counteract these factors.[2]”

Nkrumah’s presence in Guinea and the support he drew from the Guinean State came at a cost. The government of the National Liberation Council closed the Ghanaian embassy in Conakry. Ghana’s diplomatic mission was recalled.

But none of these moves seemed to have bothered either Nkrumah or Sekou Touré. Whiles in Guinea, Nkrumah continued to reach out to Ghanaians through radio broadcast. He would talk about returning soon to Ghana and putting to death all military leaders. “I know that when the time comes, you will crush the new regime. I know the Ghanaian people will remain faithful to me as well as to my party and my government.[3]”

Sekou Toure piled up the pressure. “20,000 Guinean ex-servicemen who had been in the French Army, as well as 50,000 soldiers recruited from women members and youths of the Guinean Democratic Party” would be going to Ghana “in military convoys to help the Ghanaian people free itself from the dictatorship of the military traitors[4]”, he declared.

The NLC was on the edge. It did not take Nkrumah’s words lightly and believed in the possibility of a countercoup d’état. For instance, a soviet trawler was arrested off the Takoradi harbour as there were fears that the Soviet Union/Russians were working towards the removal of the NLC.

The above background paints a fair picture of the state of relations between Ghana and Guinea, and the political climate in Ghana. It is, therefore, not hard to see how anyone from Guinea may end up being viewed with suspicion.

The protagonist in this story was a young man by the name of Salifa or Salifu. The law reports named him as Mohammed Abdul Rahim Baba Salifa. The newspapers of the day named him as Abdul Rahim Baba Salifu. For this piece, let’s call him Salifa.

Salifa was a fifteen-year-old schoolboy sent to Guinea by his father in 1965 to study. Two years later, he ran away from his guardian. He run away because he was being maltreated by his guardian. This was not out of the blue. He had previously complained and written about the maltreatment he suffered at the hands of his Guinean guardian – Dr Oury. His father had letters to show. There was, therefore, an established pattern of abuse and mistreatment. So, he chose to flee.

He did not come to Ghana directly. His first stop was Sierra Leone where he asked the Ghanaian High Commissioner to help him return to his parents in Ghana. He got the help he asked for. But not in the way he expected. He arrived in Ghana in June 1967. But once he touched down, he was arrested by the police and detained at the Ussher Fort Prison. He was not charged with any criminal offence. He was just imprisoned. He was home but could not get home. The law report did not give any reason for his arrest. Neither did the newspapers. It was widely rumoured and believed that he was being held simply because he had arrived from Guinea. Others rumoured that he might have been an agent of the Nkrumah sent to deliver some messages to Nkrumah loyalists in Ghana.

With his son at the Ussher Fort prison, his father attempted to do the very natural thing: get his son out of jail. A year after Salifa’s detention (i.e., in June 1968), his father engaged a lawyer to compel the prison authorities to produce his son. A date was scheduled for the hearing. The Director of Prisons showed up. He had a decree signed by the Chairman of the National Liberation Council supposedly authorizing the arrest and detention of Salifa.

With his son at the Ussher Fort prison, his father attempted to do the very natural thing: get his son out of jail. A year after Salifa’s detention (i.e., in June 1968), his father engaged a lawyer to compel the prison authorities to produce his son. A date was scheduled for the hearing. The Director of Prisons showed up. He had a decree signed by the Chairman of the National Liberation Council supposedly authorizing the arrest and detention of Salifa.

Salifa’s lawyer challenged the validity of the decree issued by General Ankrah on the grounds that the decree was undated and not gazetted. Salifa’s lawyer, John Lynes an Australian who had come to settle in Ghana and would eventually be deported, argued that the decree did not mention Salifa’s name and therefore it could not have applied to him. The learned High Court judge, Anterkyi J agreed with Salifa’s lawyer and concluded that the decree authorizing the arrest and detention of Salifa was faulty and not compliant with the National Liberation Council’s own proclamation. On that basis, Salifa was released.

Salifa’s lawyer challenged the validity of the decree issued by General Ankrah on the grounds that the decree was undated and not gazetted. Salifa’s lawyer, John Lynes an Australian who had come to settle in Ghana and would eventually be deported, argued that the decree did not mention Salifa’s name and therefore it could not have applied to him. The learned High Court judge, Anterkyi J agreed with Salifa’s lawyer and concluded that the decree authorizing the arrest and detention of Salifa was faulty and not compliant with the National Liberation Council’s own proclamation. On that basis, Salifa was released.

But not for long.

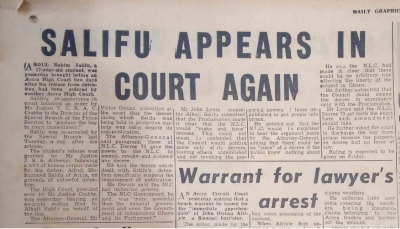

He was immediately re-arrested and brought before a different court. The first case was handled by Mr. K. Gyeke-Darko, a Principal State Attorney, who was famous for prosecuting several coup plot trials. In the re-arrest proceedings, the Attorney-General, Victor Owusu, and the Director for Public Prosecutions were in court. The presence of the Attorney-General and the Director for Public Prosecutions sums up the importance the NLC placed on this case.

Mr. Victor Owusu, as quoted in the 11th July 1968 Daily Graphic, argued that the NLC government had unlimited powers and  was “more powerful than the colonial government and even the Government of independent Ghana and its Parliament”. Long story short, the NLC could not whatever it wanted to do, including arresting a seventeen-year-old boy without charge and lawful basis. The second court, presided over by Justice V.C.R.A.C Crabbe upheld the validity of the same detention order, and Salifa was behind bars again. And this is where the story ends.

was “more powerful than the colonial government and even the Government of independent Ghana and its Parliament”. Long story short, the NLC could not whatever it wanted to do, including arresting a seventeen-year-old boy without charge and lawful basis. The second court, presided over by Justice V.C.R.A.C Crabbe upheld the validity of the same detention order, and Salifa was behind bars again. And this is where the story ends.

We only get an insight into Salifa’s thinking in a letter he wrote to his father. In his own words he writes:

“Please, father, I will like you to know that when I was coming I reported myself to the Ghana High Commissioner in Sierra Leone that I am a seventeen-year old student who has been to Guinea in 1965 October (i.e. during the old government) and wanted to come back to Ghana and stay with my parents, where I will be able to continue my studies. Well, this man (the High Commissioner) gave me a ticket, prepared my travelling certificate and helped me to embark into the plane for Ghana – with all my loyalty I am arrested.

Everything is clear, I think, that if I were coming to do something against the government I would not have passed through the Ghana High Commissioner in Sierra Leone, but, as I said, I am destined to be arrested. So, leave everything to God, father.

Please, whenever you receive a letter from Oury saying that I have run away, take that letter to the Special Branch (C.I.D.) with my letters which tell you that I am in prison in Ghana, so you have come to beg them torelease me because I am innocent and I am a student, I am not interested in politics.”

Captured in the above letter is a complex and conflicting set of emotions. Salifa asserts his innocence, comes to terms with his circumstances, attempts to console the father, and somewhere in there wishes that his guardian in Guinea Dr. Oury will write to the Ghanaian authorities to corroborate his story and hopefully get him released.

Not much is known of the fate of Salifa. Did he die? Did he survive the turbulent periods in incarceration? How long was he there? Was he eventually released? Did he finally get to know the charges levelled against him? What kind of life did he live afterwards? It is hard to tell. It has been past half of a century since the events described in this piece took place. And sadly, Salifa’s story is still waiting to be told – in full.

***: I wish to thank Mr. Fui Tsikata of Reindorf Chambers for his thoughts and insight on the subject. Also, my gratitude goes to Oliver Barker Vormawor and Ama Asare Korang for reviewing earlier drafts of this piece.

[1] [1968] GLR 630

[2]Keesing’s contemporary archives, March 12-19, pg. (21275) http://web.stanford.edu/group/tomzgroup/pmwiki/uploads/1408-1966-Keesings-a-EYJ.pdf

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

![]()

Samuel Alesu-Dordzi is an Editor of the Ghana Law Hub.